The Four Inevitable Stages of Writing A Book

In No Way Prompted By My Forthcoming Book Project on August 5th

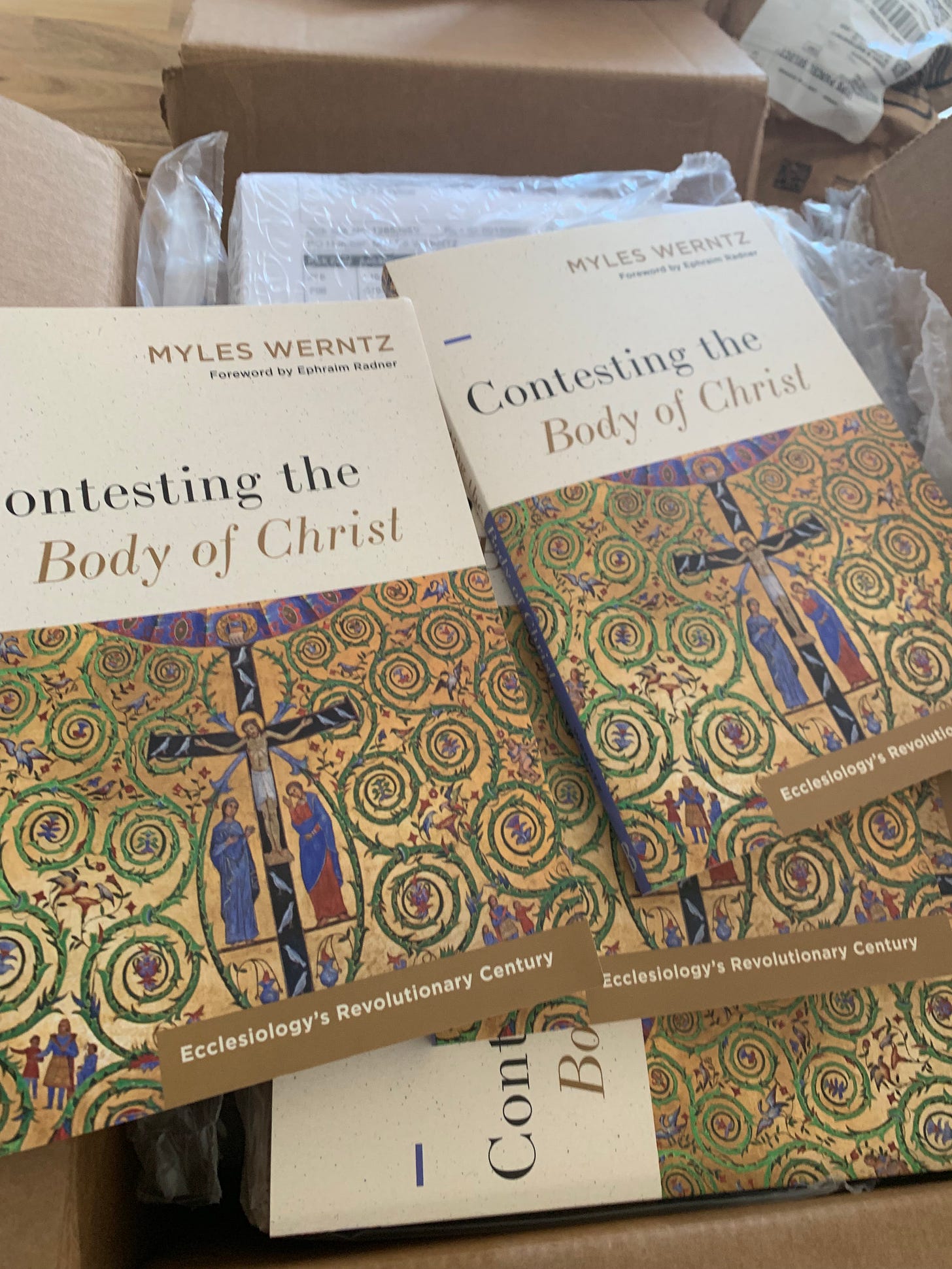

As my 8th book drops next month, let me pull back the curtain on how a book project comes together. Become an annual supporting subscriber, and I’ll send you the new one for free.

So, You Think You Have a Book In You

First, seek medical attention.

Secondly, you might very well have a book in you! Or multiple books! There’s no way to know, but be warned: they tend to multiply. Every time that I get to the end of writing a book, I have the same thought: “I don’t know that I have anything left to say”. And then, I go read some things. And then, I think “What if….”

That “what if” is a dangerous phrase: the inevitable next thought is that there should be a long string of words and thoughts after that first little thought.

But here’s a quick decision tree of next steps to help:

Sometimes, all that happens next is a brief conversation with someone over dinner, during which they’ll shrug their shoulders, and you’ll move on with your life. Sometimes, they’ll give a “Huh”, which might mean that there’s something else there that needs unpacking, another question behind the first question.

If the second thing happens here, it still might not be a book, but maybe the opportunity to create some scribblings in an abandoned notebook beneath the refrigerator manual, in the desk drawer in the living room. If that happens, don’t worry: you’ll forget about the scribblings and find them five years later when you’re moving, and you’ll scratch your head trying to remember the context or what on earth “lemon cheeseburger” meant.

Or, it could be the first post in a Substack newsletter. Or a letter to the editor written in Crayon. Or your first swing at a popular publication.

But if the thoughts keep growing, and multiplying out, and if it feels like an insatiable itch that other people get interested in watching you scratch, it might be a book1.

Step One: Have An Amazing, Audacious Idea

To write anything longer than a text message is an act of madness. I have two kids, a day job, and a whole personal library that stares me in the face every time I sit down to chip away at the book project that I’m spending hundreds of hours on. Why on earth would I do this? No one reads whole text messages, much less books.

Answer: because I have an amazing, audacious idea. That’s it. The idea sometimes comes fully formed, an answer to a question that needs to be written down and shared with the world, and sometimes, it’s more of a question that’s been posed better than others. But at it’s core, one starts this process because you think you have something that is 1) amazing, and 2) audacious.

Anyone who writes a book who tells you that they don’t think their idea is amazing is lying to you. It’s possible that there are cranking out the next thing because it’s the next thing: I’m fairly sure that James Patterson doesn’t think that every book he writes is a winner. But for the most part, the very act of stringing words together over more than 100 pages is an act of madness, unless you think you have an idea capable of sustaining that kind of writing.

Ideas—audacious ideas—need room to breathe. And this is where books come in. A literary medium like a book offers space to settle in, to nurture cul-de-sacs and asides, to build up supporting tendons and capillaries that feed into the one beating heart, the audacious idea.

Step Two: Begin To Write, and Realize You Are Entirely In Over Your Head

Of the five books that I’ve authored or am currently authoring, two of them nearly didn’t finish. Both of them are lucky to be alive, precisely because they were great ideas that were nearly impossible to execute.

The first one was my co-authored introduction to Christian nonviolence, which proposed nothing less than to introduce and sort through nearly 50 years of Christians writing and reflecting on the whats and whys of Christian nonviolence. A simple but audacious idea. This simple and audacious idea took nearly three years and countless drafts to write, and I’m very proud of it.

The second one is the one that is coming out next month, a book I proposed because I had a simple, audacious thought: “I want to write about how the church changed in the 20th century.” Only after I agreed to write it did I realize what I’d gotten myself into, and how insane that idea was. Stupidity gets up early while good sense is sleeping in. And so, before good sense wakes up and had a cup of coffee, stupidity had downed three Red Bulls, read a stack of books, gotten hopped up on bravado and written a book proposal. Seven years and two very long pauses in the writing later, it’s done.

When this happens, don’t freak out. You are on the cusp of a great adventure that might kill you. The worst that can happen is that it does in fact kill you, in which case, your literary heirs will have an amazing adventure of their own to sort out, trying to piece together what on earth you meant by “lemon cheeseburger.” But chances are high that you’ll despair for a while, take some deep breaths, sit your butt down in the chair, and work your way out one thought at a time.

Step Three: Finish a Terrible Rough Draft

By the point you finish panicking, and sit down enough times to poop out something longer than an article but shorter than a Congressional bill, you’ll have what Anne Lamott called “a shitty first draft”. It’s okay: anyone who has finished a book has written at least one, and they’re fine. They’re lovely little urchins, belched up on the shore by a loving Leviathan.

But at this point, no one else is going to love it.

You are the parent of this monstrosity, and so, of course, you’ll have affection for it. You will turn a blind eye to all of the passive voices and em-dashes. You’ll ignore the leaps in logic and the half-clever parts of writing, bad tattoos that mean something to you because you remember why a green falcon belching fire is cool.

When I wrote this book, I wrote a really awful first draft in about six weeks. It was the early days of COVID, and I had something of an idea about isolation and Bonhoeffer. So, with anxiety and coffee, I cranked out 40,000 words in short order, at which point I was convinced I had birthed a masterpiece. Unfortunately, I had the even worse idea to send to my long-suffering editor at Baker Books, Bob Hosack. Bob graciously worked out with me over email what this insane pile of pages was supposed to do, offered a contract, and the next seven months was spent pulling out of that pile of pages something resembling a book.

Last week, in cleaning up my office, I came across a folder stuffed with draft pages of this book, which I glanced over fondly for a few minutes, and then threw in the garbage. No one needs to read that part.

Editing down your intuitions is a process of giving voice to relatively inarticulate grumblings, the act of letting the rider get a hold of the elephant and wrestle it to the ground before it hurts someone. There are most likely good things in your words at this stage. You’ve made it through the wall of anxiety and put words into being! But most of the words are probably not great words, and most of what are great words are probably in the wrong place.

Step Four: Abandon Audacity, and Then Resolve Into Modesty

Once you’re past that final point, and have wrangled the whole thing into something resembling a coherent work, you’ll have spilled a lot of blood. You’ll have hacked off limbs of your lovely urchin, grown new parts that are better than the old ones, and pulled the whole thing across several miles of desert in order to bring this gift to the altar.

Once you get it there, your audacious idea now resembles something of a more modest offering, far less world-changing than honest and far less amazing than fine. And fine is….fine. At some point, you come to terms with no book living up to its potential, with no thought being finished or as deep as you’d hoped, or as filled out as you’d like. But the kids need your attention, the dog is hungry, and that yard isn’t going to mow itself.

You’ll come into a place of acceptance that you have done your best. You have offered what you have to God, and it will be burned up in the end. The good thing about ashes, however, is that they get into everything: they don’t come out of the carpet, despite multiple cleanings, and if you’re lucky, the ashes will take up residence in the lungs of your readers, in ways that won’t know about for years. Your words will become part of people’s thinking in ways they won’t recognize, and in ways you couldn’t have anticipated.

And they’ll begin again, to grow new thoughts.

I’m so sorry.