“Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies”—Psalm 23:5

The Gifts of God Not Only For Ourselves

The 23rd Psalm evokes an important question for the moral life:

What does it mean that the goods of the moral life come to us in contentious circumstances, that the rod and staff appear in the dark, that still waters require keeping wolves at bay or that the feast happens with our enemies present?

Answering this well means ruling out a number of approaches, most of which presume that something evil must exist in order for good things to occur. This way of thinking undermines the moral life as well, for this would mean that the moral life exists only because of sin, that the moral life is something which God threw in after sin forced God’s hand, and that prior to sin, there was no such thing as goodness or morality.

But this is to get things backwards: goodness does not require sin to exist for goodness to be goodness. Rather, in a world filled with darkness, wolves, and enemies, the moral life takes on new texture, and the gifts which God gives to help us navigate the world now appear not only as gifts, but as tools of repair. Let us consider that God’s gifts have always had this dual nature. Work in the garden was given not just to beat back an unruly world, but that through work, we might become the kind of people we were meant to be.

Likewise, our obedience to God pre-existed sin, that the humans might become more of what they were created to be. But now, these tasks do more than aid the people of God: they participate in God’s repair of the world. The children of God will always be given what they need for their goodness to flourish, but that flourishing is not for their own sake: it is that through them, the nations might be blessed. The moral life was always one built on communion, on gift, on sharing: this aspect only becomes more apparent now that there are those who do not wish to share in the good things of God.

The good way that the Shepherd has eternally led his flock into is one which is first and foremost for the benefit of the creature, that they might live in communion with God and with creation. The shared worship, relation, and work, given first in the garden, remains fitting for creatures if only because this is what it means to be a creature who lives well in God’s world.

That it has additional texture now—that of winning over our enemies—is just an added bonus.

The Gifts of God Refused

These many gifts of God, given amidst darkness, are routinely refused, not only by our enemies, but by God’s own people! But because they existed when there was only light, before there were such things as enemies, we cannot measure the moral life and its excellence solely by whether or not our enemies receive the gifts, or by whether they cease to be enemies. John’s Gospel, echoing Genesis 1:2, reminds us that the presence of light frequently does not mitigate the opposition; in fact, as John reminds us, it may in fact amplify opposition. For there is much darkness which remains the wild deep, the tehom (Gen. 1:2), untamed by the light, and the goodness of the moral life is not to be measured by the degree of its capture.

This is one the great follies of much modern ethics, that goodness is meant to be measured by its effectiveness, as if the way of virtue was able to measured quarterly. The crucifixion of Jesus, the death of Samson, the defeat of Israel: none of these glide seamlessly into success, and so, the ineffectiveness of goodness will have its day. For goodness is not to be weighed according to whether it keeps the darkness forever at bay: as we have seen, darkness accompanies the moral life until that time when there is no more night.

In many ways, the value and effect of goodness is largely available to us in retrospect. Goodness is that which cannot be measured by data points or graphs, but that which is measured by its likeness and resemblance to its exemplar. No manner of evil, in other words, can be mistaken for good, no matter how much benefit it results in. Goodness’ benefit is something which is only known in the end, for even that which dies on the surface may be alive in the roots, and even that which dies at the roots may be raised up to life again. It is with this reason that the moral life is marked by repentance: we might have eaten as enemies for years, without any sign of life, only to have all of our catalogs of wickedness overturned despite our best intentions.

Enemies, in other words, will win. The wicked will flourish, the Phillistines will taunt, and the Romans will endure. But none of this is reason to assume that the moral life is to be valued by whether it brings an end to our enemies. The Psalms pray nearly without end for God’s deliverance, and at times, for God to slay the wicked. But this desire—embedded as it is within the rhythms of Israel’s prayer—runs up against another affirmation: that God remains patient with God’s enemies out a desire for conversion.

It falls to the people of God, then, to be the witnesses of this patience. No one ever said this was fair.

The Origin of Enemies

There are two consistent themes which run throughout Genesis, where enemies and darkness first appear.

The first of these is that all of that which opposes God’s goodness is not ultimate. Whether we speak of the serpent in the garden, or of the darkness pushed back by the light, these are not oppositions which somehow made themselves, or opposing forces which exist as God’s equal. This does not somehow negate the damage that is done, or take the sting out of an enemy’s fight, but to remind us that they too are frail creatures of dust. The dust rises up again and again in Genesis to reclaim the wicked, from the serpent condemned to remain close to it until death to the dust billowing up over Gomorroah. Though it takes time, it does not take forever.

If the first theme deflates enemies, reminding us that the power of the enemy is not as ultimate as it pretends, the second theme draws us close to them. For over and over again in Genesis, the enemy is described as a separated family. From the very beginning, when the man and the woman are described as now being in a perpetual contest of authority and power, they still desire one another. Cain and Abel, in whom we first encounter murder, show us that enemies are often literal brothers, that two who share so much know how to wound one another well.

We see this dynamic of family-as-enemy play out over and over again, until finally, the enemies make families of their own: Ishmael, the child of Abraham, founds his own family who will be the antagonist of the house of Issac and Jacob. We helplessly watch as Jacob’s children reach out to their cousins, not to make peace with them but to sell their brother into slavery to them. It is as if the cosmic realities of tehom keep popping up again and again in the dynamics of people, the wildness of the deep endlessly stirred up as family feuds.

Christians are committed to the unity of all humans in God’s creative act, which gives no easy out when it comes to the question of enemies. It is not as simple as saying that our enemies come from somewhere other than God. And yet, over time, separation builds itself out in cultures and histories. Ishmael, son of Abraham, is sent into the desert, where he is blessed by God and creates a parallel world to the children of Isaac. The Gentiles, loved as they are by God, are not drawn in by Israel so much as develop other gods, while still bearing memories of their true home in their consciences and their bodies.

There is a difference, even here, between having an enemy and growing one, which is the difference between enemies as an accident and enemies as an intention. To face opposition for being a nuisance, mean-spirited, or not reading the room is not being persecuted. Being nice is not the same as being holy, and being a boor is not the same as being bold. The kind of enemies which the flock has are largely not, in other words, the kinds of enemies that it wishes to have or that it intends, but the kind which find the people.

The people of God are to be known as those who do what they see the Son doing, those led by the Spirit who always attests to the Father and the Son. And in doing this, the people make enemies, in no small part by not trying to be resistance or opposition to people so much as witnesses to the Lord.

The Story of Three Tables: Flipped, Eaten At, Dined With

If we are to be prepared to be this kind of people—those capable of refusing to make enemies, even if we still have enemies—we have to reckon with what it means that, in the presence of the Shepherd, there are still enemies. Particularly, we have to ask what it means that it might mean that God might have enemies.

There is a tradition within contemporary Christian thought which takes antagonism as central to our common life, that part of being a witness is to seek confrontation with the things and people causing Death’s long shadow to expand in the world. Far from envisioning the table as that place where the people of God engage in patient dialogue with their enemy, this tradition calls on a very different table: the moneychangers’ table, flipped over by Jesus. For here, it would seem that the way of the people of God is that of purely saying No, of casting out, of rewarding Death with a firm No of opposition.

There is an error of politeness which the people of God can make, in refusing to call an enemy an enemy. For not all things are yet friends, and there is a kindness of clarity in saying No. There is no prize for refusing to render judgment on that which God has found wanting, no virtue in Jesus refraining from saying that corrupting the temple was just that.

But this table flipped—confronting the bearers of Death—is not the only tables we find, nor the last tables we seek.

The table here in the Psalm is another kind of No. Having passed through the darkness of death, the flock receives its reward of dining with the Shepherd while his enemies look on longingly. The captives, led before the tired banquet guests, are not invited to partake of the feast, but to look on in jealousy. I say jealousy because, while there may be hatred here yet for the ones eating well, the food itself remains delicious. The gifts of God, enjoyed now by only the flock, are looked at in longing by those who are yet enemies.

The gifts of God pass first, we see, to the Jew and then to the Gentile, first to Abraham and then to all the nations of the world. But first is not only, for every gift which circulates in the world has one who receives it first. Here, too, the feast which is laid before the people of God is not for them to hoard, like manna in the wilderness. Rather, it is daily bread, to be given and given again by God that others might share in the feast. For it is this dynamic, of Israel sharing food with the Gentiles, which enables the Moabite Ruth gleaning the fields of the Jewish Boaz, through which she enters the line of Jesus. It is this dynamic of Gentiles sharing Jewish food that we find again in the Canaanite woman sharing the Bread of Life. In time, first becomes “not only”.

But all Nos, as one Christian thinker put it, find their Yes and Amen in Christ.

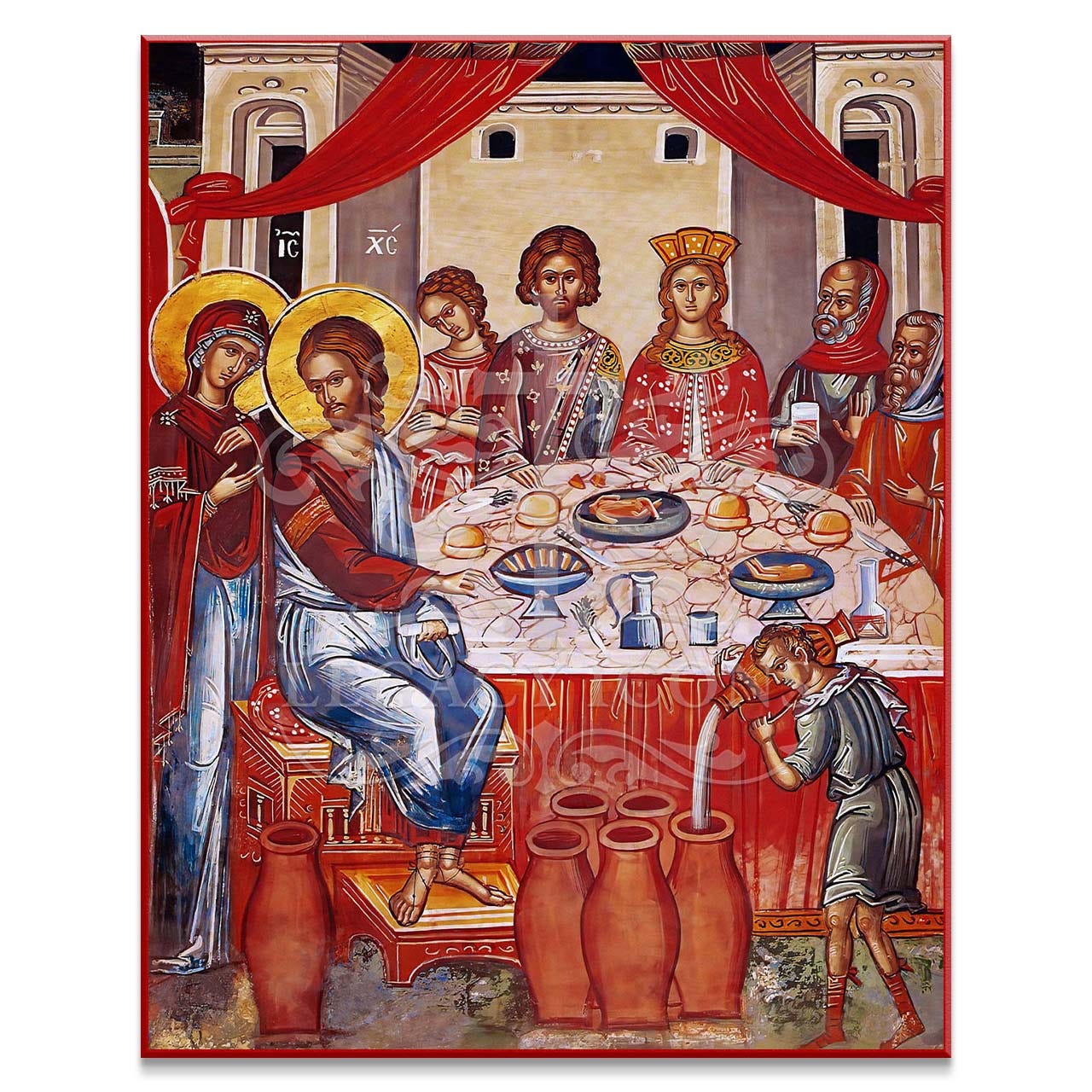

For if the first table says No in order to clarify what cannot be, and the second table says No as a way of saying “not yet”, the third table brings those who have been far away near. Jesus, in eating with his disciples the night before his death, eats with two betrayers, sharing bread baked from wheat gleaned from the field, partaking of a banquet which Gentiles will soon share in but not yet. At that table, Jesus does not cast out Peter or Judas, nor does he make them watch from afar, but dips bread in their bowl while speaking to them plainly. That they will be Jesus’ enemies—for a time, or for all time—does not prevent Jesus from sharing a table with them. The eating with enemies here takes its final turn: the No remains, and the truthful speech is upheld, but is enveloped by an everlasting commitment of God to continue eating with even those who are his enemies.

Preparing For Enemies

Knowing that God goes before us opens up the question which has been with us throughout: what does it look like to follow this God?

Given that enemies will happen, but that we do not know when or who, our attention must turn to how we prepare. As we have seen, our journey with God is one which is accompanied by desire: we go places that we want to go, not only those we are commanded to go.

Being ready for enemies, thus, cannot simply take the form of knowing a command, but cultivating a desire. As we see above, knowing what the Scriptures say, and being inspired by saints and heroes of the past is an integral part of the journey. But it cannot alone overcome the hurdle of loving those who not only are opposed to us, but might seek us harm. The problem is quite ingrained: that no one, it seems, naturally loves those who are opposed to them. Admitting this is to confirm what psychologists and sociologists have told us for centuries: we feel affection for those near us, and less for those who are strangers, much less enemies.

It is telling, then, then the Good Shepherd does not enjoin the people of God to simply remember or to think on the examples of others, to be inspired once a year by the witness of Martin Luther King Jr. One could do worse, I think, that following the example of King himself, who knew that responding to hatred and opposition was a matter of habituation, practice, and discipline. Far from it being some miraculous overflow of human goodness, King knew that love of one’s enemy only came by being opened up to God’s own love, and through practice. As we see in the words of Jesus, the way to our enemies begins with practice and prayer. In taking up the burden of those who are our enemies, not responding to violence with violence, and giving of our possessions, we begin the reorientation not only of our minds, but of our practice.

Practice, in turn, works its way into those things which we desire. And so, to this ongoing practice, we are enjoined to pray for our enemies, that in that, we might love them. All of this takes a lifetime, but fortunately, Christians—not fearing death—have all our lives to learn how to mirror the God who feasted with his betrayers.

Eating With Our Enemies

Of the having of enemies there is no end, both as persons and as a collective people. Christians, in reflecting on what it means to live well amidst violence, have uniformly emphasized that the enemy is to be loved, even if the enemy permanently remains an enemy. For if, in having an enemy, we lose our capacity to love, we lose our capacity to recall that the vocation of the people of God is to be ministers of reconciliation.

For it is in loving one’s enemy that we find the heart of God’s relation to a violent world, loving that which murdered the Son.

It is in being fed by God, with the enemy plainly in view, that we see that trusting in God and following in the way of God is not contingent on peaceable circumstances. For what draws the enemy and the people of God together in this banquet feast is that both are there because of the Shepherd: the enemies of the Lord and the people of God both persist by the same God, in the hopes that desire for what the Lord provides might be the first step to desiring the Lord’s other dining companions.

If enmity enters the world through our eating, gorging ourselves on the tree of knowledge, with violence entering the world over whose offering that the LORD would devour first, then it is fitting that the sign of reconciliation is that of a meal. The figure runs all the way down: that meal which we refused to have in the garden is the meal which the LORD himself is, and the meal which we offer to our enemies.

The feast which is offered here, interestingly, is not yet one which is shared with our enemies, but one which we eat in their presence. The LORD cooks a meal of infinite luxury and our enemies have to just watch us eat it: it is the most delicious of images, particularly for a suffering people who have passed through Death’s shadows and lived on grass and water. It is a meal offered not just to nourish, but to make jealous the enemies of the LORD.

For it is jealousy of the meal that opens up the gateway of desire: the flock knows that desire is itself the entrypoint to desiring that which is the LORD. And so, displaying the feast in a way which entices and makes hungry becomes the way not just of enjoying the LORD’s provision, but of witness: we are provided for, and that provision becomes the occasion for the nations seeing that the good which the LORD provides is meant to be theirs as well.