Just Causes, Unjust Suffering: The Witness to the Kingdom

Violence and the Spiritual Life with Howard Thurman

In the first two installments, we’ve examined how Augustine looks at the Sermon on the Mount, concluding that the life of virtue is inseparable from two things: 1) being willing to suffer the unjust for the sake of justice, and 2) the use of force against the unjust is made mostly impossible for Augustine. Today, we’ll turn to a 20th century thinker on this question of virtue and violence, Howard Thurman.

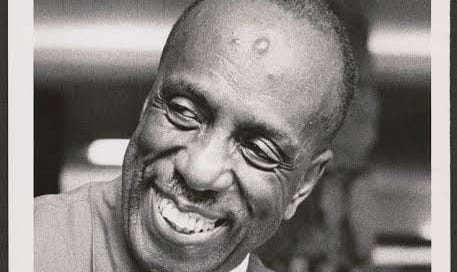

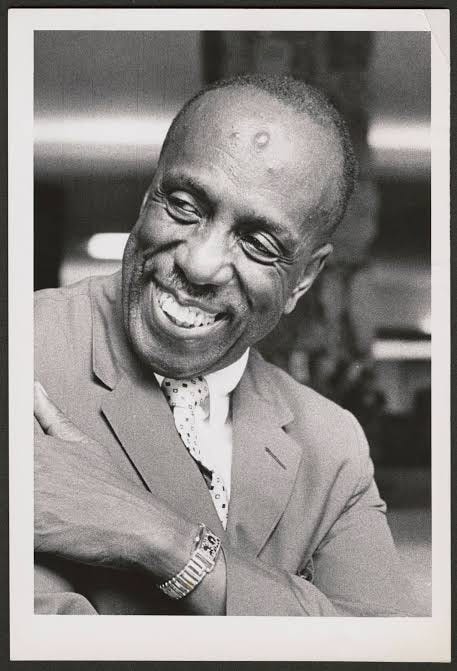

Howard Thurman, Civil Rights Saint

If you’ve never heard of Howard Thurman before, you’re not alone. There was a mini-revival of his thought a couple of years ago, with a PBS documentary and the publication of his complete papers, but he remains a far lesser-known light in the popular imagination, both Christian and otherwise. I wrote about his work here in the Christian Century, if you want a quick intro to this enigmatic figure.1 A mentor to King, the rumor was that King carried around a copy of Thurman’s Jesus and the Disinherited: whether this is true is less interesting than seeing the way in which Thurman left his imprint on the spirituality of King’s thought.

In our book on Christian nonviolence, David Cramer and I describe Thurman as offering a vision of mystical nonviolence, which requires a bit of brief unpacking. Thurman’s works assumes, as we saw with Augustine, that the primary work when it comes to addressing suffering in the world is the work done in the soul. We come to encounter God with closed hands, and it is only through prayer that our hands become open, not only to being able to receive God but to receive the neighbors who we sometimes call our enemies. Fear haunts us at every turn: we fear losing the ones we love, our property, our own lives. But it is this fear that is turned out by love, a love which enables us to embrace our enemies.

If you come to Thurman looking for strategy and tactics for addressing violence and social injustice, you’ll come away sorely disappointed, for this is not his primary interest. If anything, Thurman—a lifelong pastor and chaplain—was invested in the kind of capacious encounter with God which Augustine’s treatment of the Beatitudes exemplifies: in the end, it is more important that we see God than anything else. But like Augustine, the question of violence and the flourishing of the unjust was never far away.

The Lived Experience of the Sermon: Love of Enemy Learned Through the World

Augustine begins his commentary of the Sermon by looking at the logic and grammar of the Sermon, eyeing the ways in which the text of the Sermon yields up a vision of the soul’s ascent to God. Thurman begins inductively, by asking what we learn of the Sermon through the experience of suffering itself:

Many and varied are the interpretations dealing with the teachings and the life of Jesus of Nazareth. But few of these interpretations deal with what the teachings and the life of Jesus have to say to those who stands, at a moment in human history, with their backs against the wall.2

That Thurman is writing these words in 1949, making the connection between the African-American lived experience and New Testament studies is striking enough, but Thurman goes on: because Christianity has forgotten that Jesus was Jewish, it likewise has forgotten the normativity of suffering which Jesus knew. Jesus, a “poor Jew” in Palestine knew not only economic privation, but what it meant to be a “member of a minority group in the midst of a larger dominant and controlling group.”3

But whereas others will take this experience of oppression and suffering as reason to not take the Sermon at face value, Thurman ran the other direction:

The striking similarity between the social position of Jesus in Palestine and that of the vast majority of American Negroes is obvious to anyone who tarries long over the facts. We are dealing here with conditions that produce essentially the same psychology. There is meant no further comparison. It is the similarity of a social climate at the point of a denial of full citizenship which creates the problem for creative survival. For the most part, Negroes assume that there are no basic citizenship rights, no fundamental protection, guaranteed to them by the state, because their status as citizens has never been clearly defined.4

Jesus embraced none of the options available to the oppressed: withdrawal, assimilation, or resistance. Rather, he rejected the hatred of the enemy which corrupts the soul, and taught his followers to embrace love of the enemy:

Jesus rejected hatred. It was not because he lacked the vitality or the strength. It was was not because he lacked incentive. Jesus rejected hatred because he saw that hatred meant death to the mind, death to the spirit, death to communion with his Father.5

Like Augustine’s treatment, Thurman too emphasizes the priority of the damage which violence-making and hatred-having does to the soul. What is fitting for the soul dictates what is done in the body, as a witness to the Kingdom of God which emerges through the bodies of those willing to suffer injustice, both for God’s sake and for the sake of the unjust.

Refusing Violence for the Sake of the Violent, Not the Oppressed?

It is here that the emphasis on soul-work which bears itself out in suffering the unjust comes full flower: the Christian—even the oppressed Christian—for Thurman is ordered in their refusal of violence toward the healing of the oppressor. In a series of sermons collected as The Growing Edge, Thurman notes that people are creatures of habit, such that those committing violence are “the victims of all the forces that play upon their lives, shaping and modeling and fashioning them…the hated one is a ever a victim of the predicament of his life!”6

Again, the emphasis within a situation of violence is on the one doing the violence:

When I have a personal enemy with whom my sense of community has been ruptured, I must put aside my blindness, my conceit, my arrogance. I must find the person, talk it through, feel it through, think it through, and arrive at a climate of understanding that absorbs the rupture and restores the primary intimate character of our relationship. When I have done that, then I can go before my God in one piece.7

The confidence here is staggering, that one would be so secure in one’s relationship to God that the enemy and their healing would be the concern. And in this way, Augustine and Thurman see together. And it is here that enables Thurman to go further than Augustine, in putting aside the possibility of violent correction of the unjust, to remember that God infinitely values the soul of the enemy, to whom God gives rain and sun undeserved.8

Augustine, I argued, leaves himself little to no room to run with respect to applying violence to situations of injustice, opting to counsel Christians to suffer injustice for the sake of the unjust, in imitation of Christ. Thurman will extend this line of thinking, more explicitly in the direction of nonviolence: Christ understood this situation of unjust suffering intimately, and is thus able to counsel us authoritatively in this way.

Taken together, it’s a compelling vision which thickens significantly a reading of the Sermon which looks purely to the tactics of the Sermon, or to how nonviolence might be deployed as one act among others: for both of them, the love of God for our enemies means that this act of refusing to take up arms against the unjust is to promulgate the perfection of the soul into public.

But by now, one of the lingering questions with respect to this vein of reading the Sermon on the Mount should be apparent: What about third-party suffering? In their descriptions, the emphasis here on suffering injustice presumes that the Christian is the one suffering, and that they are suffering for the sake of converting the unjust. But this doesn’t quite get to some of the big questions of nonviolence’s efficacy, or of how this relates to the suffering of others.

In the next edition, I’ll take this up, asking not whether Augustine and Thurman should give up their ground, but how this position they’ve carved out addresses this lingering question. This will be a subscriber-only post, but like a Tinder relationship, you can always try it out for a week before committing.

Paying Attention: Jon Askonas writes on the ways in which a post-truth world disintegrated, beginning not with Tucker Carlson, but with Jon Stewart.

Also, Jon on why conservatism failed (hint: $$$$$$)

In the spirit of the criticisms raised by Jon, why do Christians continue to engage uncritically in the bleeding edges of technology?

I find myself drawn to these kinds of complicated, less than straightforward figures: Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Dorothy Day, Howard Thurman, Augustine. As one who by temperament tries to hold together disparate positions and try to reconcile them, I appreciate these lights from the tradition who likewise do the same. For you Enneagram nerds, I’m a 9 through and through.

Jesus and the Disinherited (Boston: Beacon Press, 1996), 11.

Ibid., 17-18.

Ibid., 34.

Ibid., 88.

The Growing Edge (New York: Harpers, 1956), 6.

Ibid., 9.

Ibid., 12.