Some housekeeping: The deal for paid subscriptions, in which you’ll get one of my recent books for free, continues til the end of the month! And don’t forget the upcoming book club on September 18th, on Thomas a’ Kempis’ Imitation of Christ.

**

Anger is the River of the World

To name how anger works, we have to begin with what anger is, how it moves and where it comes from. Before there is analysis of it, it appears among us, in the Psalms, in the stories of Genesis, in the mouth of God: it runs through the cosmos as a feature of what it is to live in a world in which aspirations and desires do not come to fruition.

Anger is, in its most basic form, the response we have to something we care about perceived as being out of joint. The anger we feel at being cut off, at someone being denied proper care or justice, at our children not listening: these are all forms of this primal emotion which tells us two things.

Something We Care About is Not as It Should Be.

This basic awareness tells us something, but not everything. When I am angry at nearly being hit in my car, my rush of anger is simultaneously about my car, my own safety, the safety of my children, the financial insecurity of getting into a wreck. It is about all these things at once, including possibly anger at myself for nearly making a huge mistake, for not following further back. It is a sense of judgment rushing up from the depths both at another agent, at the world, and at myself. I can, later, pull these things apart, and begin to ask questions about the anger, but in the moment, anger ties the world up into a knot and presents the problem as simply wrongness and pain.

The Wrongness Is Not Immediately Fixable.

When I am cut off in traffic, and the blood rushes and my senses flare, it is not only because there is Something Wrong, but because that Something is not immediately fixable. Anger comes with a recognition of our impotence of the immediate problem: my children cannot be compelled to listen, nor the driver in front of me to drive more safely, nor police to be unbiased in their judgments. It does not mean the Wrongness is somehow less wrong, but that the Wrongness exceeds my immediate grasp.

In the cases of large things, this means that the anger may be insoluble: say what we will about scalable solutions of poverty or climate change, good solutions will always displace the problem rather than irreversibly resolve it. More traffic lights will mean fewer wrecks, but slower commutes and more exhaust expended. More funds for public schools probably means higher graduation rates, but expands the dubious assumption that high test scores mean a person is skilled or capable of employment. .

To name both of these things—both the injustice and its scope—it part of the work of recognizing what anger presents to us. And to that, we should be grateful. Anger is always with us, in no small part because injustice and Wrongness is always with us, in small and large ways. And thus, we grow angry but are enjoined not to sin in our anger1, or to be slow to anger2, but it would be folly to suggest that somehow anger was able to be eradicated.

But herein lies the trick: this river, beneath us and before us, is a trickster. It tells the truth in part, and withholds the whole, because what we see is part of an ancient flood running into deep canyons I know nothing of, and contributing to small estuaries I will never see. My anger at unsafe drivers is directed at the car in front of me, but runs backward to the Eisenhower administration and its design of the Interstate behemoths, bumps along through the use of interstates to crush black communities, and will run forward to how interstates increase the climate crisis. The driver in front of me is the focal point of a larger river that will outrun me and outlive me.

The Problem With Cultivated Anger

And thus, the problem with hoping that anger can be cultivated or channeled. Melissa Florer-Bixler, in her How To Have An Enemy3, proposes the following:

In communities of shared anger we discover lingering within us our own participation in the destruction of others. Anger, like a fire, can offer light which illuminates the form of destruction that are active within our own lives and communities…Because the church is a community of reconciliation, we recognize that we bear both victim and victimizer in our bodies…When anger binds us together, revealing and burning away, it becomes holy.

Florer-Bixler’s book is arguing against a kind of cheap reconciliation which refuses, among other things, to have enemies, or to recognize that there are things about which Christians should be angry. And this is true: anger is, as I have argued here, an indicator of Wrongness, and thus, anger is something to pay attention to. The river tells us a partial truth. Anger, in its appearance, directs us to one aspect of the Wrongness, but by obscuring another. It points us toward the driver in front of us and obscures the bigger question of why these roads persist.

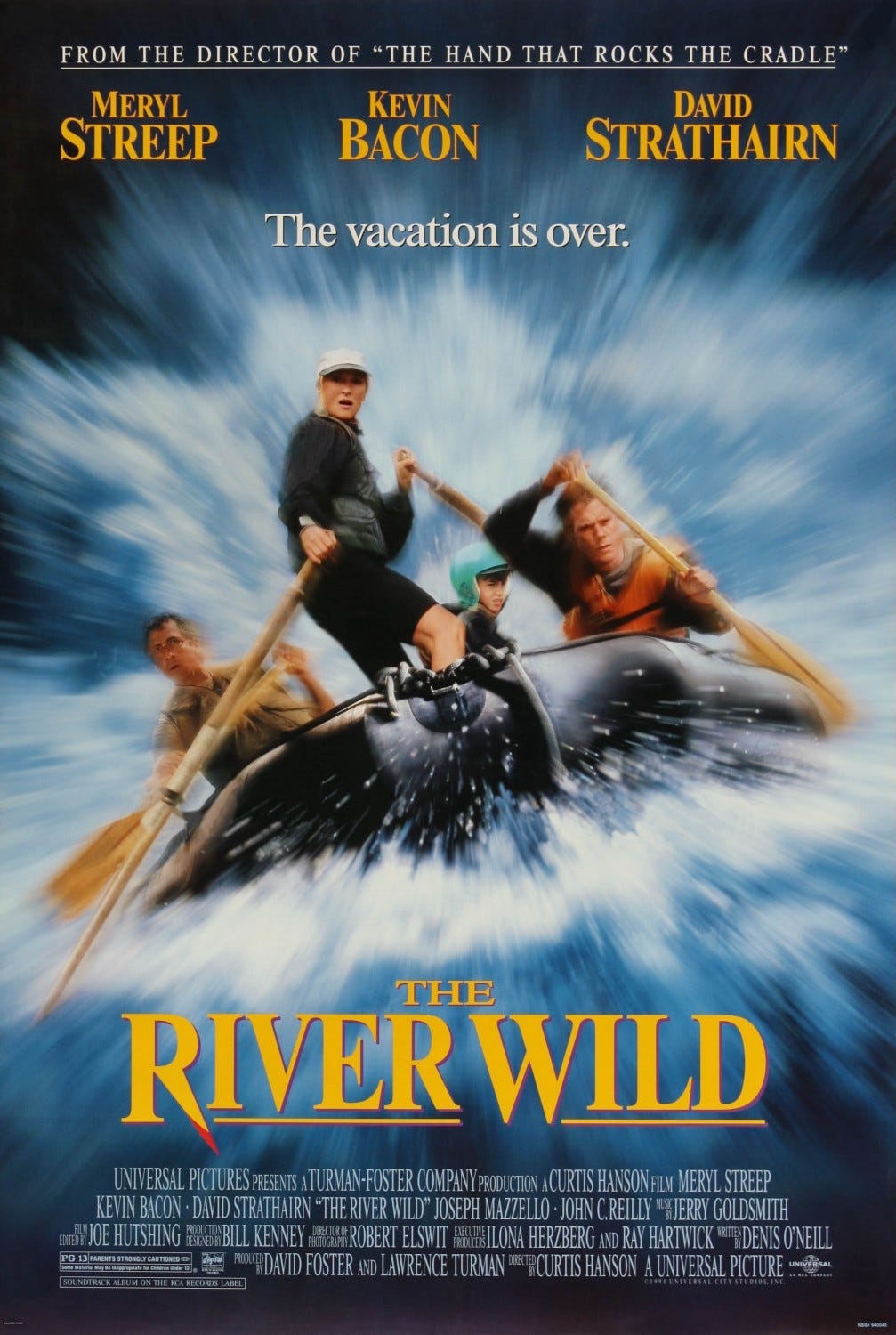

My point is, however, that anger needs not be cultivated, organized, or binding, that ultimately, if the anger is a river flowing through the land, of small injustices seen because of large injustices, the river cannot be tamed, and it will not bind us together. The river is a malestrom, and the strongest swimmer will ultimately drown in it. If we cultivate some small pool or eddy of the water, and think that this means we have cultivated anger, we are awaiting to be overwhelmed, because there is always more water coming, and anger will always win.

Florer-Bixler’s work is best seen, I think, as a call against apathy and a call for churches to have clarity about their commitments. But anger, once organizing us, does not make us holy, for the holiness of God is one in which anger operates as an indicator and a guardrail, and not the thing itself. If anger is a wild river, then God’s use of anger is for the sake of illuminating and awakening, but not cultivating. The anger of God is not that which we are to share, but that which points us away from that which is not to be shared, that which is killing us: it is not an organizing principle, but that which we encounter as a wild torrent unrestrained. None of this, of course, means that complacency is the way forward, only that anger is not that way.

Between Bureaucracy and Rage: The Future of Anger

So, let us put aside talk of cultivating anger. Once anger opens us to the reality of Wrongness, once it provokes us, what is there to do?

Option 1: Give it Voice

The voice of anger, because it can see the eddy we live in, but not the river’s depths forward or backward, is that of the present: we are angry at this specific thing, though it may have deeper roots. And as such, the best word for anger in this form is rage, an eruption which is evoked by a particular moment.

This song, well sung, is not a great song. It captures a strong sense of despair and rage, but as rage, does not hit its target. It has listened to anger, tried to channel it, and in channeling it, has tried to listen to the depths of anger, naming systems and structures and patterns of power. But its anger and target miss wide, and in missing, misdirect us about the river undergirding its anger.

The song speaks truthfully, in that it speaks from Oliver Anthony’s experience of buying and selling his labor. But, as Neil Postman reminds us, television cannot speak the truth without dissembling as well: the depictions of the powerful obsessed with knowing the activities the weak is more apt of the very Internet companies which made him an overnight hit than it is of Congress.

And yet, we’re off to the races: anger, unfocused, becomes rage, and rage will be harnessed by those who know that rage is great for furthering modest, incremental ends. That Dan Boingino jumped at the chance to produce Anthony is a case in point of bad actors thinking that the way to social change is to channel rage into some kind of anger, thinking they can control it.

Option Two: Institutionalize It

The instance of Boingino illustrates the shadow version of anger management: institutionalization. If giving free range to anger is one variety, trying to make it part of the operationalized DNA of a movement is another. This variety misunderstands what Anthony knows well: there is no point of rage beyond itself; it does not make us holy or offer a politic—it expresses.4

Once anger is brought into the house, it will direct what kind of house there is. Once it becomes the operational virtue, it will move load-bearing walls, carve out the floors, and determine how we spend the money for the light bills. The institutions which attempt to hold it have to, by their very definition, be flexible to hang on to its motion, or be themselves left behind by anger’s flux.5

Anger lives among us, activated as a sign that something which we love is under threat. And that thing which is under threat may be true or false. And our assessment of how it is attacked may be true or false. We are fallible creatures, and thus, anger is not somehow a sagiac prophet but a wild river, in touch with half-truths and possibilities. Anger is that which puts in touch with questions worth asking, but is itself not the answer to be sought through sacrifice, offerings, or rituals.

Ephesians 4:26

Proverbs 16:32

There is a reason why, I think, as much as I like Rage Against the Machine, it’s never launched a political program.

There is a reason why populist institutions built on outrage are never able to conserve or progress enough, and are in time eclipsed by the more conservative and more progressive: there comes a conflict between the need to hang on to the animating anger and the need to provide longitudinal stability, and the need for the organizational structures to survive always win.

Oliver Anthony's bit is classic folk,

singing to its own choir

but, ultimately, reaching none past

a final note.

Very Guthrie/early Dylan-esque.

Sadly, our cultural memory

and attention span

is no longer as tight or as lengthy

as it was in their hey-day.

The book I read aboutChristian anger was Unoffendable by Brant Hansen. He looked at every instance anger was mentioned in the Bible and noted it usually was quite violent, burning, crashing, etc much like a river with class V rapids.