Keywords of the Moral Life: Gluttony

The Baseline of All the Vices, And the Renewal of the World

Gluttony, and all of its friends. And like all vices, the private and public intersect. Reminder: if you sign up for a paid subscription before the end of the month, I’ll send you one of my recent books as a thank you.

The Body and Political Destiny: Or, Boo All Nazis

What I want us to entertain for a moment is that there’s something to the dictum that “the personal is political”, but not in the way we think. There is a way of hearing this oft-used phrase and using it to subordinate all of what you are to political ends: that the entertainment we partake of, the people we date, the broccoli you splurge on—it all Says Something Bigger than what kind of vegetables you prefer. It says something, the story goes, about the kind of world you want to see.

What I want to suggest is that this connection is right, but backwards.

**

In Philippians 3, Paul depicts his opponents not as ignorant fools, but as those who can’t help themselves in their desires to fall down the stairs after themselves:

For, as I have often told you before and now tell you again even with tears, many live as enemies of the cross of Christ. Their destiny is destruction, their god is their stomach, and their glory is in their shame. Their mind is set on earthly things. But our citizenship is in heaven. And we eagerly await a Savior from there, the Lord Jesus Christ, who, by the power that enables him to bring everything under his control, will transform our lowly bodies so that they will be like his glorious body (Phil. 3: 18-21)

It’s a curious formulation that Paul puts forward here, in part because our way of identifying the moral life does one of two things: piety and the political are kept at arms length by some1, and piety and the political are collapsed together by their mirror image2. Paul, however, maintains a distinction and connection between the animating piety of his opponent, and their political destiny.

So, on the one hand, the one who awaits for their “lowly bodies” to be transformed, is the one who waits for the Lord to bring everything under control and who has in mind citizenship. Their opponent, by contrast, has a different political vista—destruction and shame—as indicated by the deity who takes residence between their belt and their ribcage. In both cases, the political contrast—the cosmic and macro-public destiny—is linked to the state of personal piety, without collapsing one into the other.

The body is a sign of political destiny.

Now, this can go to some really dangerous places, particularly because this aphorism of “the body is a sign of political destiny”—when taken in terms of materiality—is not too far from what the Nazis held.3 If we believe that the body is a sign of one’s political hopes, not only are you pretty concerned with super-healthy, super-virile people, but you’re also attentive to whether or not the people around you are the kinds of bodies that you take to be compatible with living the good life.

But what Paul links together here is precisely that our bodies—strong or weak—are all lowly in light of their transformation by the Spirit, not into ubermensch but into saints. For just before this, Paul had exalted not the Greek gods, but Epaphroditus as exemplary, a man who co-labored with Paul and nearly died from it

But I think it is necessary to send back to you Epaphroditus, my brother, co-worker and fellow soldier, who is also your messenger, whom you sent to take care of my needs. For he longs for all of you and is distressed because you heard he was ill. Indeed he was ill, and almost died. But God had mercy on him, and not on him only but also on me, to spare me sorrow upon sorrow. Therefore I am all the more eager to send him, so that when you see him again you may be glad and I may have less anxiety. So then, welcome him in the Lord with great joy, and honor people like him, because he almost died for the work of Christ.

The language of care and evocative language—particularly in light of Philippians 2:5-11, which describes Jesus as the one who suffered and died and was exalted—hammers home this distinction of the body as the locus of God’s work, but not because it was potent or strong. The body remains significant in God’s economy not because it is through human bodies that the renovating power of God marks out space in the world—not as ephemeral and mystic presences, but in and through the peculiarities of human life, most particularly the ones which resemble the crucified and risen Jesus.

Beginning with the Stomach: The Headwaters of Vice

Here, I want to turn to The Conferences of John Cassian, which offer a compelling window into how the desert Christian monks of the 4th century lived the spiritual life. Like other works of this era, their point is not to provide an exhaustive compendium of any and all sins: this would fall to much later writers like Thomas Aquinas to tease out the moral psychology of the vices. The point of the Conferences is to tease out what it means to be virtuous.

But this isn’t to say that the Conferences are simplistic. Much later, it would become commonplace to note that all virtue is one: if the aim of the holy life is to be singular in one’s pursuit of goodness, then all the virtues which we could possibly ennumerate are all ultimately pulling together as one. But vice works similarly for the Conferences: the classic vices of anger, acaedia, lust, covetousness, and so forth are all linked together in a chain, such that to have one is to have some of the others, even if you don’t know it yet.

For example:

In order to overcome acaedia, you must first get the better of dejection; in order to get ride of dejection, anger must first be expelled; in order to quell anger, covetousness must be trampelled under foot; in order to root out covetousness, fornication must be checked, and in order to destroy fornication, you must chastise the sin of gluttony.4 (Conferences 5, ch. 10)

You can see how this works: a person suffering from acaedia (sloth) needs to get rid of the notion that there’s nothing they can do about their lives and rise to the occasion. But to get rid of that, you have to get rid of resenting your lot in life (anger). Anger is caused by thinking that we’ve gotten a bad shake, and we want what we don’t have because we want the wrong things wrongly (covetousness). But to get rid of that, you better tackle your burning desire to satisfy the lusts of the flesh. But to do that, you need to tackle the root of it all: gluttony.

It’s strange to say that gluttony, the habitual overindulgence of appetites, is at the root of all kinds of other vices, particularly when pride is usually the prime culprit. But gluttony here is the root because it’s the place where the habits of the undisciplined body begin to emerge. It’s a small step from living for bodily pleasure to desiring pleasure for its own sake, being angry when your comfort is thwarted, and finally despairing because pleasure and satiation will always been one step out of reach.

Renewing the World: Beginning with the Stomach

What strikes me as so revolutionary about the Conferences is that they point us to a very simple, but very profound truth: that through the body, the world is remade. One of the tragedies of the 20th century was the way in which the body became a stand-in for greater ideological battles, with individuals not seen for their political affiliations.5 But the way to recover this is not to sever the connection between piety and politics, but to see that whatever world of piety is to be rebuilt—what shape the kingdom of God will take in the world—it will do so in and through the renewal of bodies.

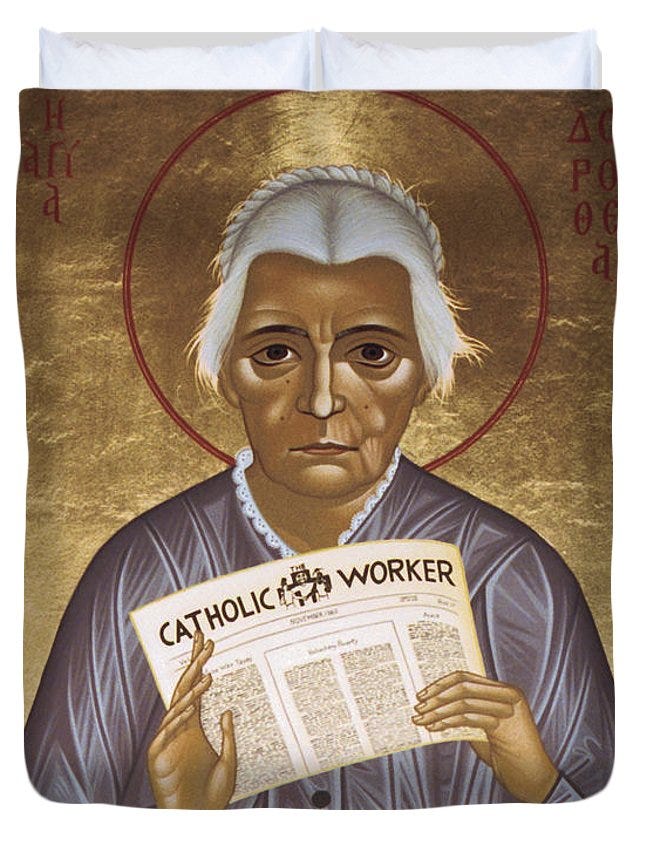

Dorothy Day, following the lead of Therese of Lisieux, emphasizes this when she writes that

When I sit in jail thinking of war and peace and the problem of human freedom, of jails, drug addiction, prostitution and the apathy of great masses of people who believe that nothing can be done--when I thought of these things I was all the more confirmed in my faith in the little way of St. Thérèse. We do the things that come to hand, we pray our prayers and beg also for an increase of faith--and God will do the rest.6

It’s less fashionable to talk about personal piety, as linked as it has become with [your favored evangelical movement to dog on here]. But this is a distraction to the real question, which is this: the claim of the Christian faith is that your bodies matter, and that the renewal of our virtue is central to how the renewal of all things works.7 That we die is beside the point to this vision, for we are creatures who will be raised up again: what we are as humans—and all of the character that we are—becomes iconic for the Big Work of God.

Gluttony, then, in all of its mundane form, becomes all the more significant: it gives birth to far more glossy vices, with far more dire consequences. But I can’t honestly think of a more dire consequence than trading away the birthright of Israel for a bowl of soup, of trading God for sex, of waking up after fifty years and realizing that all the concessions to ease and pleasure have left me looking wistfully at the foothills, having known only the intimacy of my recliner very well.

By this, I mean the kind of politics which would describe life in the world as a matter of the practicable determining what counts as virtuous: what works is, crudely put, what counts as virtue. There are various iterations of this, but the point is that it treats piety as something which may or may not matter in rational calculations of statecraft.

To subsume what a person is into their effectiveness politically is a different kind of problem, but ultimately a mirror image: if dividing off piety for the sake of rational calcuation is one problem, pretending that a person is only as good as their political action is to say that whatever piety you have is a matter of group luck. Some forms of pious action just aren’t available to people, and saying that a person’s piety is a matter of pious action is laying a weight on them and then not helping them lift it.

It’s also prominent, not accidentally, in the Very Online New Right’s thinking: why are all the would-be Nazis promoters of exercise and nutritional supplments? Because you have to be virile enough and healthy enough to procreate the new super race, and to be able to defend one’s own people against the racial and cultural outsiders. The organizations New Founding and American Reformer were, in my mind, recently nailed to the wall for harboring this very kind of evil, and once again, the defense of the wicked was “they’re just really into promoting healthy living and anti-obesity!”

Pride and vainglory kind of work by themselves in a different family tree.

In this new book, The Godless Crusade, Tobias Cremer posits that it’s no longer ideologies which spur on reactionary movements, but identity: the union of persons around common traits and characteristics. I think he’s right, though I still need to read his argument carefully to sort out the details.

For all of the fashionability of writing about Dorothy Day as social reformer, her traditional piety is consistently an embarrassment for her more recent biographers.

I’ve been reading Andrew Davison’s Christian Doctrine and Astrobiology, partly because I have a soft spot for the possibility of intelligent life elsewhere, and partly for review. Whether or not the Conferences are right about how all this works for whatever else there is, I’m not sure, but I’m enough of a realist to agree with G.K. Chesteron’s line that if you go to the farthest moon, you’ll find written behind its sun “Thou shalt not steal.”

Loved the Dorothy Day reference!

Your post reminded me of William Cavanaugh's idea that there is really no transhistorical religion that can be separated from politics. Christian piety, then, is essentially a revolutionary political stance.

Somehow (and I don't believe in coincidence) I am coming into contact more and more frequently with teachings on the importance of the body, and positive bodily activity in the world -- that is, the importance of humans using their God-given agency for the betterment of the world and their neighbours. Somehow (I won't speculate on exactly how in this comment) the subject was woefully neglected in my own Christian upbringing. This was a refreshing read for me, Myles, and you've gained a subscriber.