The Limits of Christian Advocacy in Post-Christian America

The Limits of the 20th Century Exemplars, and The Need for New Thinking

American Christian advocacy in public needs some new exemplars. But there’s one that’s always been around.

Our Poor Popular Imagination

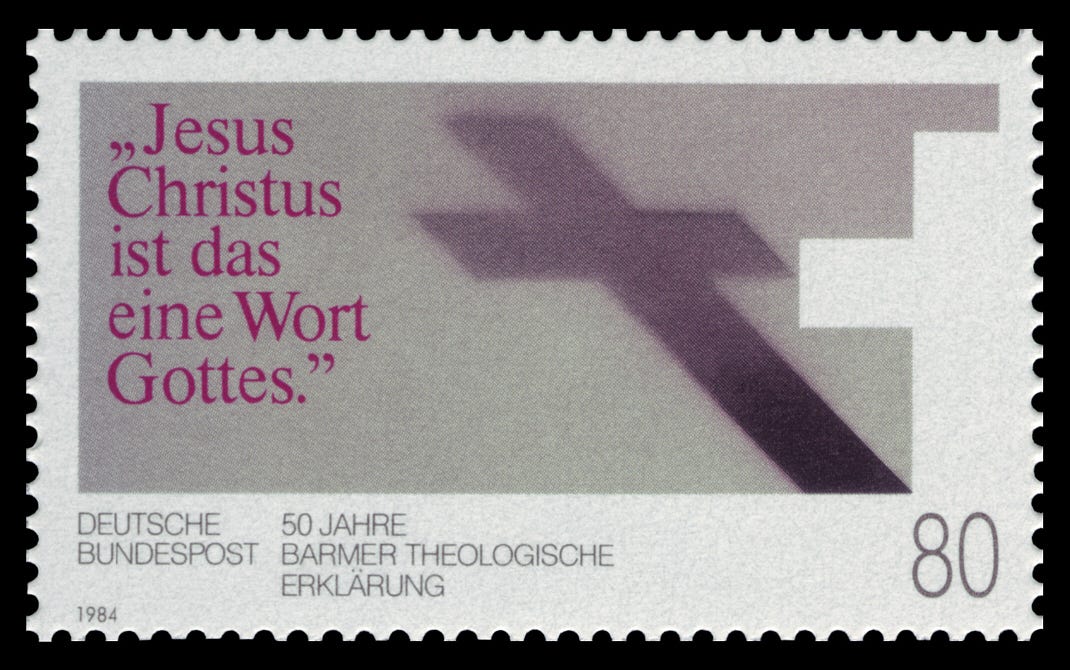

Last week, I had a piece in Christianity Today on why American Christians don’t need to try to do another Barmen Declaration. The Barmen Declaration was a statement issued by a consortium of churches in Germany prior to the Second World War, pushing back on some changes made by the National Socialists to how German churches operate, and portended a lot of disasters ahead for the church there. It has a pretty expanded reputation in historical memory, and in some ways deservedly: it sings pretty clearly what’s at stake in the church-state relationship, and it still inspires today.

But the limits to Barmen are two-fold:

It keeps to its lane, which is theological exposition. In contrast to basically every theological statement issued today, Barmen is laser-focused on theological principles, though it clearly has social issues in mind. I say this as a limit because its lane assumes that people broadly care or are persuaded by theological issues. Apart from the Gospel Coalition, I doubt any organization could write something as theologically-driven as Barmen without getting a nation-wide shoulder shrug.

It relies on a church-state relationship which does not have a parallel in America. The German nation-church arrangement was one in which German ministers were pensioned and churches were administratively overseen by the state. The Reichstag couldn’t tell churches what or how to preach, but they did oversee ordination standards, funding mechanisms, etc. As such, Barmen is keenly aware that the state is overstepping its bounds in trying to get churches to affirm the Fuhrer, or to change the rules on who can belong to churches. If there is a parallel relationship in America, it tends to be a toxic one: even the former Office of Faith Based and Neighborhood Partnerships (RIP) was pretty fuzzy—and openly biased!—in terms of who it partnered with1.

My reasons for saying Christians don’t need a new statement were basically two: 1) Barmen assumed a thick set of institutions to make the statement into a reality, and 2) Barmen wasn’t meant to be an “in the moment” kind of statement, but to rearticulate things in coherent theological fashion which needed to be said again. American Christianity lacks both of the institutions and the appetite for theological coherence to make such a statement possible.

But there is another popular example that always comes up, if not Barmen: the Civil Rights Movement, and particularly, King’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail. King’s famous letter, which I teach every year, is filled with theological allusions and explications, from Thomas Aquinas to Paul Tillich to Augustine. It works out a nuance kind of natural law argument to oppose segregationist practices and to spur white churches to join the Movement.

Whereas Barmen stays in its lane of churchly things, King freely moves from theology to public life, back and forth from church to city square and back again. But if Barmen is not possible because for the reasons named above, King’s kind of movement seems impossible because for two different reasons:

The declining influence of church in thought about public life. No need to get into the back-and-forth demographic evidence for this. Church attendance flucutates, and may yet increase again, but since the 1970s, church influence on public life matters has waned as a broad function of public imagination, and been restricted to a few key issues.

It’s fine for people to want to think in targeted aways about specific issues, marshaling particular verses for abortion or immigration, but verses function against theological backgrounds, and its the broader theological tapestry of understanding and thinking that is largely absent. Unless the government bumps up against a few third-rail issues, a Christian moral imagination has been largely replaced by a procedural (or anti-procedural) bedrock. This is why “Obey the laws!” and “Get the judges out of the way!” are what rise to the surface, rather than anything more theological or complex like what King’s letter assumes.

The loss of ecumenical relations around social issues. What King’s letter reflects is a large consortium of African-American churches from a broad theological trajectory. My first book was about this phenomenon during the Vietnam era around war. But what, anecdotally, appears is not ecumenical galvanizing around social issues, but either 1) pragmatic partnerships by specific theological traditions or 2) ecumenical gatherings around theological questions.

For the first, consider how many times Jordan Peterson has been highlighted by Word on Fire (a Catholic bishop highlighting the work of a non-Christian psychologist), as a bulwark around questions of Western heritage and gender roles. For the second, consider the Gospel Coalition—one of the largest ecumenical gatherings in North America—which focuses on theological issues solely (apart from the perennial exceptions of sex and the Internet).

It’s Always Been On The Ground

What gets obscured in these two vaunted historical examples is how these both begin in local spaces: Barmen as common concern of local pastors, and the Movement as a collection of local churches. It always begins small. It just looks like it emerged huge out of nowhere.

There are any number of other historical exemplars we could look to which speak theologically into social issues, and do so in persistent and robust ways. The trick is, that unlike these two, most of them are local and particular. Dorothy Day’s Catholic Worker houses, or the Koninia House of Clarence Jordan: these are robust, but self-consciously concieved of as witnesses in the wilderness.

I do not say that as a criticism, but as an acknowledgment that these are, I think, the way forward now. Whether a time comes in the future for there to be possible something like a King, I could not possibly pretend to say. But for now, and in all times, the possibility of something small, local, and infectious remains.

This is a smaller, and more deliberate road to take, one which emphasizes ordinary and coherent formation, and speaking in ways where the ground intersects with the Good News of God. It’s boring, and probably will be ignored in most places. But then again, history is littered with these faithful remnants: Barmen and the Movement just caught lightning in a bottle.

In a challenge to my non-bureaucratic instincts, this office has been replaced by the “White House Faith Office”. By shifting it to inside the White House, as opposed to be an agency, it now functions effectively as a propaganda arm of the executive branch. When Paula White is the face of the organization, who was hawking Easter wares for private gain, and who was under investigation for tax fraud by the Senate for four years, what was a public-facing office for partnerships is now just Rasputin on Botox.

"...What gets obscured in these two vaunted historical examples is how these both begin in local spaces: Barmen as common concern of local pastors, and the Movement as a collection of local churches. It always begins small. It just looks like it emerged huge out of nowhere..."

Emergiong from the local church, try this, a bit long at 2 hours, but worth it: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rad8Lx7MhLU&t=149s