The Measure of Virtue

Naming What Counts as Goodness, And Then Some

Virtue has a shape, but does it have a measure?

Paid subscriptions remain 50% on sale until tomorrow night.

For the last year, I’ve been in a series of seminars with several other theologians, ethicists, and philosophers to learn about psychological science. You can read more about the project here.

Yes, I’m as surprised by this last paragraph as you are.

As one who’s married to a clinical social worker, there’s persistently a gap between what we’re talking about, I think.1 Broadly, what theologians and ethicists mean when they say things like “good” is usually more metaphysically-laden than when social science and counselor types talk about it. I usually mean something like “corresponding to what we are meant to be as God’s creatures”, while counselor and social science folks mean something closer to “integrated, functioning, and generally not sociopathic.”

I initially got interested in this particular project for two reasons. One, as an ethicist, I’m always looking to broaden my tool kit, to be able to make use of other disciplines to illuminate or broaden the claims that moral theology makes. But second, the particular questions of how scarcity constricts our moral imagination—a question I’ve written on frequently here—is a really vexing one.

And so, I went for a week last May, and then again this month, to learn. It turns out that the question of whether or not we can measure things like hope, love, courage, and patience is actually pretty interesting. When psychological science says that they can measure these things, what they mean is that they can measure whether a person behaves in such-and-such a way over time, or under certain conditions. I’m learning to speak the lingo of independent variables and hypotheses, even if it’s like a second language that I’m constantly cramming in before the exams.

Broadly, as an ethicist and theologian, I’m on board with the notion that there can be certain actions which correspond to certain virtues that we have, even if I think that ethicists and psychologists will disagree on what exactly psychological measures are actually telling us. Does the fact that people have behaved in such-and-such fashion mean that they are virtuous? What if being virtuous actually looked less like well being and more like a willingness to live with loneliness and disappointment?

Christians, when they’ve talked about virtue, have talked about things like desire, motivation, the will, love, and all the rest, but the form this takes is slippery. As Jennifer Herdt has amply illustrated, the history of moral reflection is one rife with affirming the value of “fake it til you make it”, of “putting on” virtuous behavior like a shirt that’s too big until you grow into it. You can do something, and it looks all the world like the good thing, but have done it for all the wrong reasons: it’s the semblance of the thing, but not the thing.

All of this makes measuring something like virtue….tricky. You can take personality tests galore, Strengthsfinders, Enneagrams, tarot dart boards—but virtue—a long-term movement in the soul, the marking of one’s character in a decided direction toward wisdom—is…harder to measure. We can talk about growth in certain kinds of behaviors, but equating this with virtue is what happens when people have to try to explain themselves: we have to point to something, gesture toward some kind of thing in the world that looks like what we mean, even if we clear our throats endlessly.

Learning from the Abbot

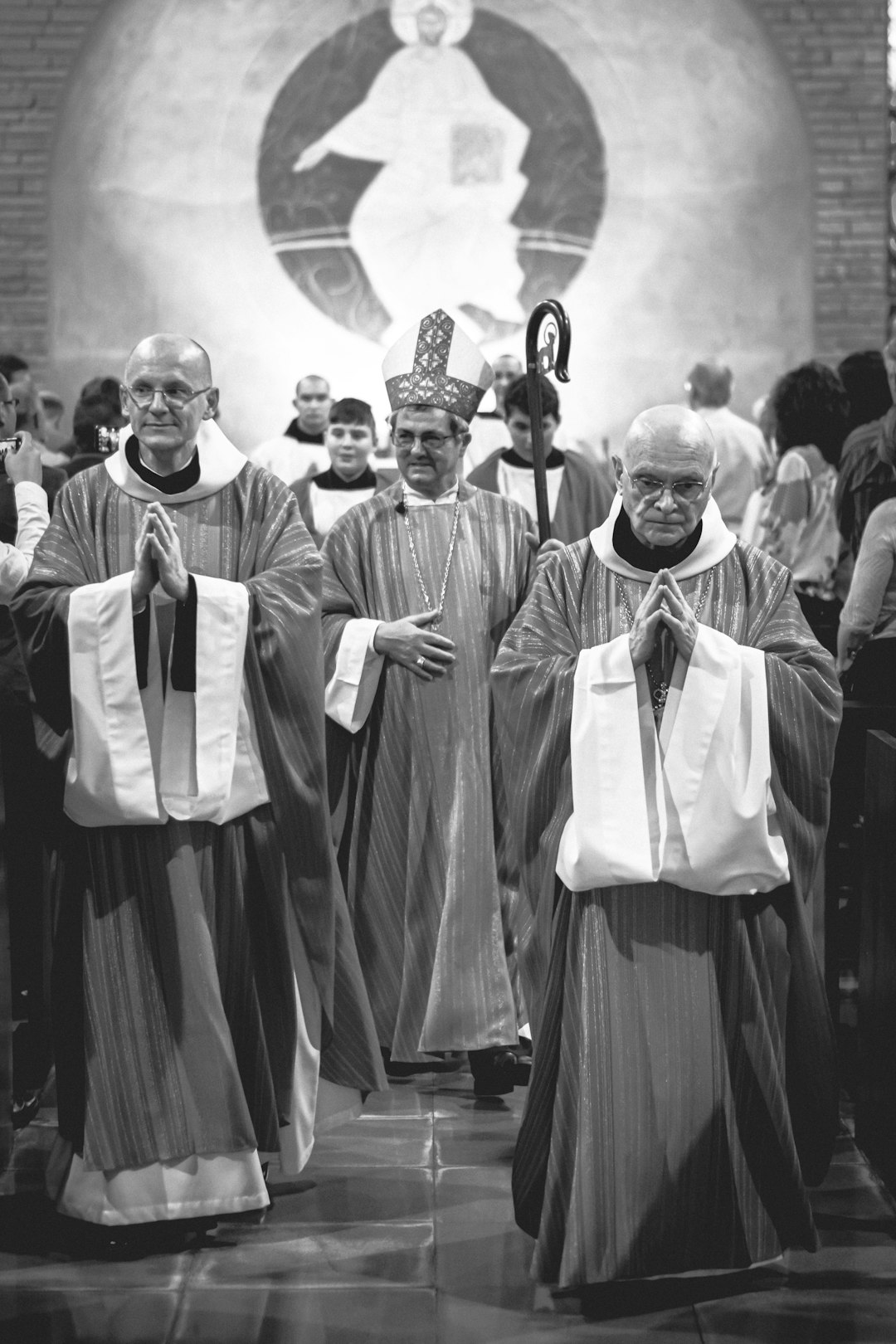

I’m in the middle of teaching a short course in Boston on church, and how church is intrinsic to not only our spiritual lives, but to our moral lives. They’re a lovely group, and tomorrow, we’ll look at Benedict’s Rule, one of the oldest and most widely read accounts of monastic life, as a model of how we become people of virtue.

The second chapter of the work jumps right in, by describing the role of the abbot, the spiritual director of the monastery. From one vantage point, starting so strongly with the abbot can be off-putting, and cause us to see the monastery as a proto-managerial organization: the abbot has ultimate direction over the activities and spiritual life of the monks, with all decisions filtering through him. Despite chapters which describe the ways in which deliberation happens among the monks, or about the freedom given to other functionaries within the monastery, the abbot retains ultimate responsibility for the spiritual lives of all else there.

The abbot is given, according to the rule, is to “show equal love to everyone and apply the same discipline to all according to their merits”, administering just treatment to all, and making use of a range of approaches to move everyone on their way toward spiritual maturity. The world of modern bureaucracy—if not tyranny—appears thinly veiled.

But this is where our assumptions about terms such as “rule” and “justice” need some challenging, beginning with this one: the rule is not a law, but a person. The abbot, as the leader of the monastery, is not an administrator, but a paragon, an exemplar who in their person provides guidance “in deed and word” of where the other monks are to go. This person is, the Rule goes, held responsible for the actions of the other monks, with their character as that which guides their actions and words.

“Justice”, then, is not so much equity as it is “what is appropriate to moving a person toward their end”. What is needed for one monk is not universal in scope, quantity, or quality: what beginners need is not what the more spiritually advanced require in terms of direction or correction, and justice requires not the same treatment, but treatment which moves all in the same direction.

All of this is the kind of thing which doesn’t fit into a spreadsheet, correspond to a survey, or fit very well into quantitative analysis. It doesn’t mean that there aren’t indicators of how certain practices, habits, and attitudes might travel together, but I take this to be different than virtue. Love, for example, has lengthy description in Scripture, but frequently shows up under contradictory signs: love is simultaneously that which causes a person to sacrifice themselves, and to preserve their own life; humility is that which might show itself in deference, and in rightly refusing the wrong plans of another.2

The vision of the abbot, of virtue as a person, takes us far away from trying to nail down the singular shape that virtue. And in particular, since the abbot is mirroring Christ in this arrangement, the example of the abbot becomes folded even further in: examples gain texture as the exemplars themselves grow in virtue. As they, the exemplars, grow in maturity, their wisdom grows and deepens as well, gaining texture, discretion, and empathy.

The image of virtue in the world, if it is rooted in the person of Christ, refracts itself through the witness of the disciples. It grows and proliferating into innumerable images which grow out into the whole of the monastery, or for us, into the cracks of all the world. And in its growth, it finds new shapes, filling out the fullness of a life—the life of Christ is the consistent source and shape of our own virtue, and since Christ is the Son, the textures of what this look like deepen in new fields and worlds unknown now to us. It’s the kind of goodness which is better understood as holiness, the imaging of God’s own life which deepens into unfathomable light, as opposed to purity, something existing along an axis of yes and no.

Such a vision of virtue is not which encompasses everything or anything, as if both love and hate could both be equal images of Christ, but all that is true expands out, gaining new stories and new refractions. May we be bearers of that life which continue to grow, until time’s end, and beyond.

This is the way with all marriages, I think: one spouse is using words and ideas in ways just off enough from the other one that all manner of hilarity and friction ensues.

If to be humble is to see oneself as in submission to God, then this would paradoxically involve refusing to submit to others wrongly.